Willem collected octopuses near Friday Harbor, Washington. East Pacific red octopus like to inhabit bottles on the sea floor (Image courtesy Willem Weertman).

Do octopuses actively use smell to find food? It seems like an obvious question but according to Willem Weertman, an environmental science grad student, there’s really no evidence to prove it. Yet.

This year, Willem is researching octopus olfaction at the University of Washington’s Friday Harbor Laboratories. His test subject is the east Pacific red octopus (Octopus rubescens), a common coastal species that remains largely a mystery because of its vast habitat and nocturnal nature.

Images of the shanty and flume under construction (Images courtesy Willem Weertman)

He’s conducting his research using a flume he built inside ‘the shanty,’ a DIY lab space he built from tarps, pipes, and duct tape.

To research the nocturnal species, Willem has become nocturnal himself. Two hours before sunset, he’ll move one of six research octopuses into the main tank to acclimate. For eight hours after the sun sets, he’ll regularly place chopped shrimp or non-scented controls on spikes in the tank. The inner area is a blackout tent, to make sure octopuses do not rely on vision during the nightly trials. He uses near infrared cameras and lights to record the octopus’s movement.

The footage is hypnotic and eerie. The octopuses are ruby-red in real life, but appear ghost-white on camera. They largely stick to the walls but, when a shrimp is placed in the tank, the scent carries on the current like smoke from a chimney. When an octopus picks up an odor plume emanating from its prey, it flows across the tank to find it in the dark.

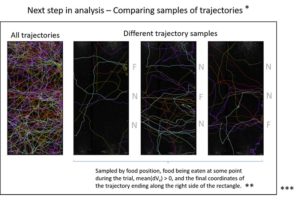

Using a new motion monitoring technology called DeepLabCut, he can estimate the location of features on an octopus as x,y coordinates, with human-equivalent accuracy. Does the octopus behave differently when there is a scent in the tank? How does it move once the odor plume passes by? Does the octopus approach the food linearly or randomly? By quantifying movement, Willem can compare actual data from test to test instead of relying on observations alone.

Colored lines indicate the octopus trajectory within the tank.

The technology involved is still new, which partly explains why octopus olfaction remains unverified. “As far as I know, no one else has ever tried to do automated tracking of octopuses to a degree where they’re tracking them continuously within a space,” Willem said. “The only reason we can do it is because of DeepLabCut and modern tools that have been developed literally in the last two years.”

That’s good news for marine scientists, who can now ask more questions about octopuses. “You look at work with rodents and flies and they’ve had automated [motion monitoring] tools since the 90s,” Willem added. “Because of that, they’ve been able to ask really deep, nuanced questions about behavior.”

Willem’s work is ongoing, but early evidence shows that octopuses do track odor plumes. Regardless of the outcome, Willem’s motion mapping thesis – which he aims to publish after graduation – will provide a building block for even more research on octopus behavior in the future.